Andrew Wilder of the excellent site Eating Rules, developed a terrific .pdf that explains how to read a basic nutritional label that you can download for free. Also, see his excellent story on reading food labels on the AttuneFoods web site.

Andrew Wilder of the excellent site Eating Rules, developed a terrific .pdf that explains how to read a basic nutritional label that you can download for free. Also, see his excellent story on reading food labels on the AttuneFoods web site.

Seattle-based nutritionist Beve Kindblade generously provided all kinds of great information for the book. She recommends keeping things simple when analyzing labels. “I always tell my clients to avoid anything with less than three percent of fiber per serving, and more than six grams of sugar or total fat per serving.” That, she notes, eliminates about 90 percent of processed food. Salt gets a lot of flack, but she acknowledges that people react differently to salt. “If you’ve got high blood pressure, aim to lower salt in food.” The best way to do that? Research shows that home cooks use significantly less salt than what’s put into processed food. “So if you want to cut down salt, cook at home more.”

Unfortunately, as Andrew mentions in his guide, food manufacturers aren’t always upfront about what’s going on inside the box or they play up stuff that sounds good, but ultimately means little. A few examples:

- Meat labeled “all natural” means nothing (until they develop a synthetic chicken easily confused with the real thing)

- Cereals are often touted as “multi-grain” to make them sound healthier, but in reality, it just means they may contain wheat and one other “grain,” often corn. Check out the Whole Grain Council’s tips for choosing true multi-grain and whole grain products)

- Eggs or chickens labeled as “free range” mean simply the chickens had some access to the outside, but it doesn’t mean they ever actually grazed anywhere except a commercial feedlot.

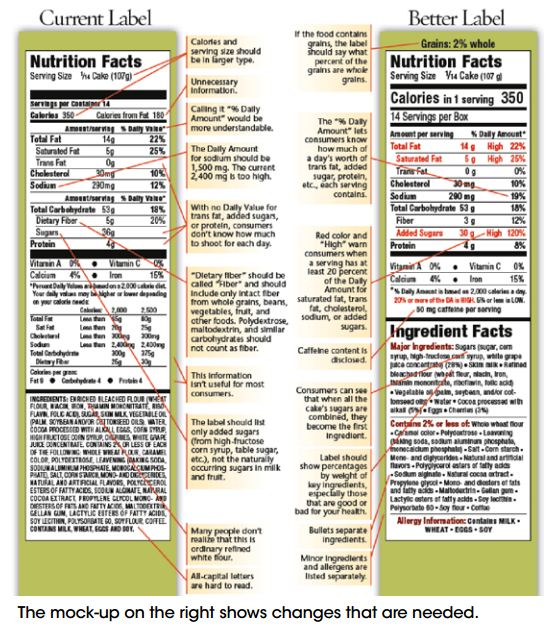

If you want to get behind the issues around food labeling, the Center for Science in the Public Interest has its own section on labeling and even published a report titled Chaos in Food Labeling, wherein they make the the case for improving the labels by requiring more stringent regulation of manufacturers prove nutritional claims, put the stats in some context and base the information on more reasonable “serving” suggestions. Also, most of the information is based on the requirements for a 2,000 calorie-a-day diet for women, and a 2,5000 calorie a day diet for men. But in reality, this isn’t true for the majority of individuals, particularly the third of Americans who are obese. For instance, at 5 foot 4 inches, my daily caloric needs are about 1,600 calories a day, according to this nifty calculator.

As professor Marion Nestle noted on her blog, food manufacturers take advantage of loopholes using a classic example: an eight ounce bottle or can of Coca Cola. Ask yourself honestly: If you open a can of Coke, what’s your intention? To drink the whole thing? The good folks at Coca Cola, however, maintain that a Coke can provides two-and-a-half servings. New labeling, proposed by CSPI and other advocates throughout the health industry, would require it be labeled as its consumed in reality — a single serving. With that, the nutritional picture changes dramatically.

By the way, with either label, soda in general doesn’t fit within Kindblade’s guidelines for sugar-per-serving.

My friend encouraged We would quite possibly like your site. It’s all very interesting, can’t wait to try some of the recipes. Thanks!!